Gabriella Rácsok

The Eucharist and Visual Culture – Editorial

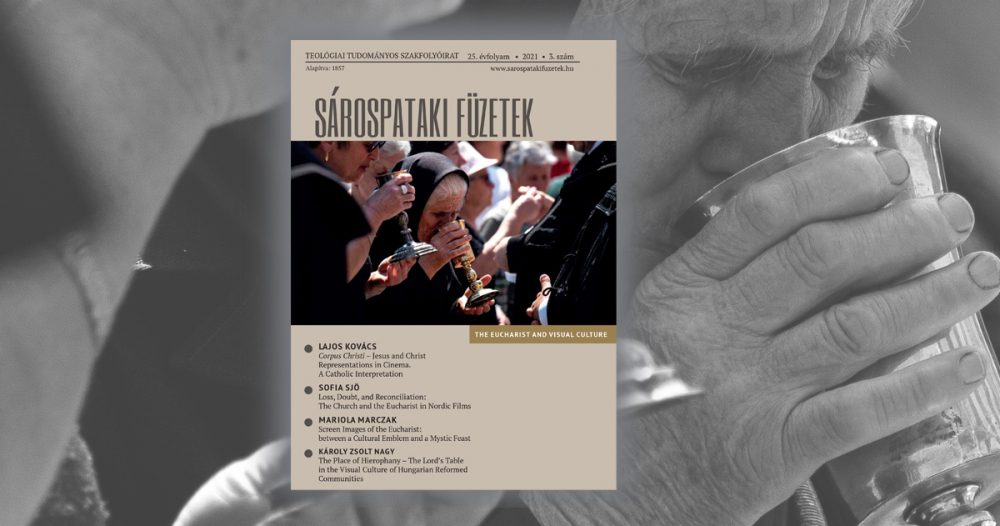

InterFilm Hungary held a conference on “The Eucharist and Visual Culture” on 1-3 October, 2021. The venue, host and main sponsor of the event was the Sárospatak Reformed Theological Academy. It was a special honour that the conference was also supported by the Lutheran Church of Hungary and the Cistibiscan Reformed Church District.

InterFilm Hungary, founded in 2020, is a member of InterFilm International. Behind the decision of the founders was the conviction that the Church could not ignore the artistic, spiritual, and social significance of the motion picture, while it must also see how the Church, religious phenomena and theological concepts affect the motion picture medium.

With the October conference, the organisers wanted to raise awareness of the potential of visual culture, which is fundamentally defining our age, and to help believers recognize the Christian messages that are being conveyed through the present “flood of images”. They hope that this conference was only the first step in building a long-term relationship between films and Christian values.

The conference included four main presentations in English, three workshops, two film screenings and related discussions. The personalities and expertise of the Roman Catholic, Lutheran and Reformed speakers guaranteed that the original idea of the conference fell in good hands: the key-note addresses by Finnish theologian Sofia Sjö, Polish film aesthete Mariola Marczak, Hungarian theologian and director Lajos Kovács, theologian and anthropologist Károly Zsolt Nagy provided the backbone of the conference. In the workshops, theologian and cartoonist Sándor Békési, theologian and church leader Tamás Fabiny, art historian Márton Orosz and theologian Gabriella Rácsok were the dialogue partners.

The diversity of the themes presented at the conference served to illustrate the many threads that connect our visual environment with the idea and imagery of the Eucharist. The first, thematic part of this volume gives a taste of this. Although the subject of the Eucharist and visual culture cannot be reduced to the relationship between theology and film, the majority of the keynote lectures focused on this topic, given the research fields of the speakers. In establishing the relationship between theology and film, there is an understandable demand that film can be an illustrative aid for theology. This can mean not only the movie adaptation of biblical stories but also the illustration of theological propositions, subjectively experienced religious truths or ethical dilemmas. In this case, theological film criticism is looking for “cinematic analogies”.[1] This also typically includes theological film criticism that focuses on the director’s intentions or biography as a religious background. The speakers at the conference sought to distance themselves from this approach that emphasizes the illustrative function and classifies cinematography as a maidservant, in which we encounter a rather static conception of theology.[2] The evaluation criteria for the relationship between theology and film cannot be determined by theology alone, for it is then tempted to see connections between film and other texts that exist only in the mind of the interpreter.[3]

Lajos Kovács’s presentation distinguishes between the cinematic representations of Jesus and Christ. In the more than century-long history of Jesus films, there have been many adaptations: there has been almost no film genre or technique that has not been tried out to tell the story of Jesus. The various adaptations have brought along various images of Jesus. We must always be aware that, in the case of Jesus films, the Scriptures do not provide complete script materials for filming the biography of Jesus. The Gospels themselves are interpretations and interpreters, with their implicit Christologies, and consequently, every Jesus film is also an interpretation of interpretations. The Jesus of the films is not the canonized or dogmatized Jesus of the Church’s faith. Lesslie Newbigin considers it true of both the literary Jesus stories of Western culture, which were created to facilitate the understanding of the Gospel, and of the pictorial representations of Jesus that they are more self-portraits than portraits of Jesus: “They told you more about the writer than about Jesus. […] one can see in successive self-portraits of Jesus the self-portrait of the age…”.[4] The same can be said of the artistic or cultural framework of representation that was prevailing at the time. William R. Telford makes a similar point about the representation of Jesus on film: “… the Jesus depicted in cinema, has been influenced by the tradition of the evangelist, the imagination of the filmmaker and the social context of the audience. […] The screen image of Jesus has varied with the shifts and currents of society itself, in line with its changing social, political and religious perspectives and values.”[5] Newbigin asks the question: “what does this gallery of portraits have to do with the real Jesus? How can the gospel ‘come alive’ in all these different cultural contexts, and still be the same authentic gospel? That is the problem of contextualization.”[6]

One of the difficulties of Jesus’ portrayal is the depiction of the dual nature of Jesus – in Chalcedon’s phrase: “vere deus, vere homo”. This Christological aspect brings us to the question of the filmic portrayal of Christ. The literature pertaining to the subject uniformly identifies a film as a Christ film in which the characters, plot or other details remind us of the story of Jesus in the Gospels, even though they do not tell it. Instead of biographical treatment, i.e., historical fidelity, the focus is on Christhood, i.e., the articulation of Jesus’ messianic mission in a historically unlimited context. We are thus dealing with a kind of contemporary cultural interpretation of the incarnation. The literature on Christ films has developed a variety of criteria to help the viewer recognise the implicit or hidden Christ figure in a film, understand when a character can be identified with Christ, and indeed what the purpose of this identification is. These lists of criteria are already extremely different in their extent, ranging from two to twenty-five.[7] However, identifying the hidden Christ-figures in film can lead to a dead end when seeking a source for Christology since the imperfect cannot represent the perfect. All cinematic Christ-figures have flaws, disabilities and sins that stem from the frailty of being human, and this can be an obstacle for the viewer in finding analogies. Rather, these imperfections allow the viewer to identify with these characters; an identification that does not help to understand Christhood but rather the following of Christ.[8] Taking this thought further, Christ-films can be seen as attempts to answer Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s question, “who is Christ for us?” On the one hand, contemporary cinematic art or popular film works can help us understand what contemporary people think about Christ and salvation, and on the other hand, as Bonhoeffer’s questioning is more directed towards this, they can open up the question of the specific Christian ethos of imitatio Christi or discipleship.

Sofia Sjö introduced the audience to Scandinavian films that can help to learn about the religiosity, beliefs, religious convictions and experiences of people today. Cinema is a special medium for expressing things that (post)modern persons are concerned about. Film as a social (communal) medium expresses the experiences and insights of a whole crew, and thus may serve as a barometer for the human condition. Film tells us what is happening in the world, not in the external (political or social), but in the internal world of human beings. This approach makes film the source of theology, from which theology can get information and turn its own reflections in the direction of urgent questions, thereby helping the church participating in God’s mission get to know the context of the audience receiving the Gospel better: what do the people of our time think about religion, faith, God, sin, grace, redemption, heaven and hell? What terms do they use at all for these biblical and theological concepts, or what content do they fill these with?

Mariola Marczak’s aesthetic approach also sees films as sources of theology (loci theologici). Film has become the main storyteller by the beginning of the 21st century. Film tells stories by presenting such human conditions and events which by means of aesthetic experience (the viewer’s being drawn into the story) may become possible alternatives for the viewer: (s)he may bring his/her own story into the film or may set it side by side or opposite to it. The mission task of the church in this situation is to help today’s individual find the biblical creation-fall-redemption narrative as a framework for meaning-making, that is, to help connect the subjective side of religion to the objective one. In other words, the mission task of the church is to point to the God-story in which human life can find meaning, that is, to point to the question of what the real story is in which our life stories are also included. This also means that although theology can rightly claim that in its formulations it understood this biblical narrative, it must give up its claim that it has fully understood or exposed this truth. All reality is interpreted reality. In view of this, we must be able to accept that interpreting the biblical narrative solely in confessional dogmatic frameworks also has its limitations. The contemporary cultural and cinematic interpretations of the biblical narrative are not, by all means, empty relativism, but may help better understanding and thus enrich the biblical text and our contexts with their fresh insights. To do this we need the ability to hear and listen to the stories of others, either that of the filmmaker or the viewer. Theology thus becomes a talk of God by its reflection on the Word of God (special revelation), while reflecting on the motives of the religious quest of humans (anthropology) and those metaphors or analogies of redemption/salvation that seem to be the most useful in understanding the biblical narrative, and which are suitably presented and communicated by films.

Károly Zsolt Nagy’s lecture invites us from the world of films to enter the walls of the church: he defines the church as “theology one can walk around in”, and uses visual illustrations to present the principles and practices of Hungarian Reformed church architecture, their art-historical implications, and the temple-related characteristics of Reformed religious practice.

In the second half of the present volume, full-time and visiting lecturers of the Sárospatak Reformed Theological Academy present current slices of their research fields.

According to Swedish film director Ingmar Bergman, whose Winter Light was a recurring theme of the conference, “a film is made to create reaction.”[9] Interactivity is an absolute requirement of our time, and dialogue must be a feature of the Church’s mission, which cannot be a one-way communication of content. “Theological discourse connects ages, people, places and relationships.”[10] Theology, then, happens where interaction takes place. Through the writings in the present volume, we invite our Readers to this happening, to this encounter.

[1] Nolan, Steve: Towards a New Religious Film Criticism: Using Film to Understand Religious Identity Rather Than Locate Cinematic Analogue, in Mitchell, Jolyon P. – Marriage, Sophia (eds.): Mediating Religion, Studies in Media, Religion and Culture,London – New York, Continuum, 2003, 169–178.

[2] Johnston, Robert K.: Reel Spirituality, Theology and Film in Dialogue, Grand Rapids, Baker Academic, 2006, 70–73.

[3] Wright, Melanie J.: Religion and Film, An Introduction, London – New York, I. B. Tauris, 2007, 20.

[4] Newbigin, Lesslie: The Gospel in a Pluralist Society, Grand Rapids – Geneva, Eerdmans – WCC Publications, 1989, 141.

[5] Telford, William R.: Jesus Christ Movie Star, The Depiction of Jesus in the Cinema, in Marsh, Clive – Ortiz, Gaye (eds.): Explorations in Theology and Film, Oxford, Blackwell Publishing, 2006, 138.

[6] Newbigin: op. cit., 142.

[7] Reinhartz, Adele: Jesus and Christ-Figures, in Lyden, John (ed.): The Routledge Companion to Religion and Film, London – New York, Routledge – Taylor & Francis Group, 2009, 431.; Kozlovic, Anton, Karl: How to Create a Hollywood Christ-Figure, Sacred Story Telling as Applied Theology, Australian eJournal of Theolgy, Volume 13, 2009/1, URL: http://aejt.com.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/158538/Kozlovik_Film.pdf Last Accessed: 2022. 03. 23.; Brinkman, Martien E.: Jesus Incognito, The Hidden Christ in Western Art Since 1960, Amsterdam – New York, Rodopi, 2013, 37–42.

[8] Pope, Robert: Salvation in Celluloid, Theology, Imagination and Film, London – New York, T&T Clark – Continuum, 2007, 104–108.

[9] Bergman, Ingmar: Why I Make Movies, Horizon, Volume 3, 1960/1, 8–9.

[10] Kuhlmann, Helga: A jó teológia mint az igazság és az eredményes élet gyakorlatának keresése, in Huber, Wolfgang (ed.): Milyen a jó teológia?, Budapest, Kálvin Kiadó, 2006, 91.